Allemagne / Années 1920 / Nouvelle Objectivité / August Sander

Centre Pompidou May 11th — Septemper 5th, 2022

Stepping into this ambitious exhibition at Centre Pompidou is to step the actual Weimar Republic. With an overly long and self-explanatory title, Germany/ 1920s/ Nouvelle Objectivité/ August Sander, this collection presents an extensive account of the overlapping narratives which framed the evolution of German modernity until its end during the rise of Nazism to power.

A period of change, the 1920s was subject to aesthetic debates in Germany that noted the gradual disappearance of fashionable expressionism in favor of a painting that returned to a form of realism out of a new detached and objective attitude after the First World War.

The New Objectivity, a term forged by art historian Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub after his famous Mannheim Kunsthalle exhibition, became a cultural slogan referring to new artistic trends in Germany. With a critical and bitter look at a society torn by war, different disciplines at the time shifted to rationality and pragmatism. The present exhibit, directs our gaze towards this multidisciplinary movement, thus depicting artworks, personalities, and utility objects of German history, linked by the Magnus opus of photographer August Sander, The Man of the 20th Century.

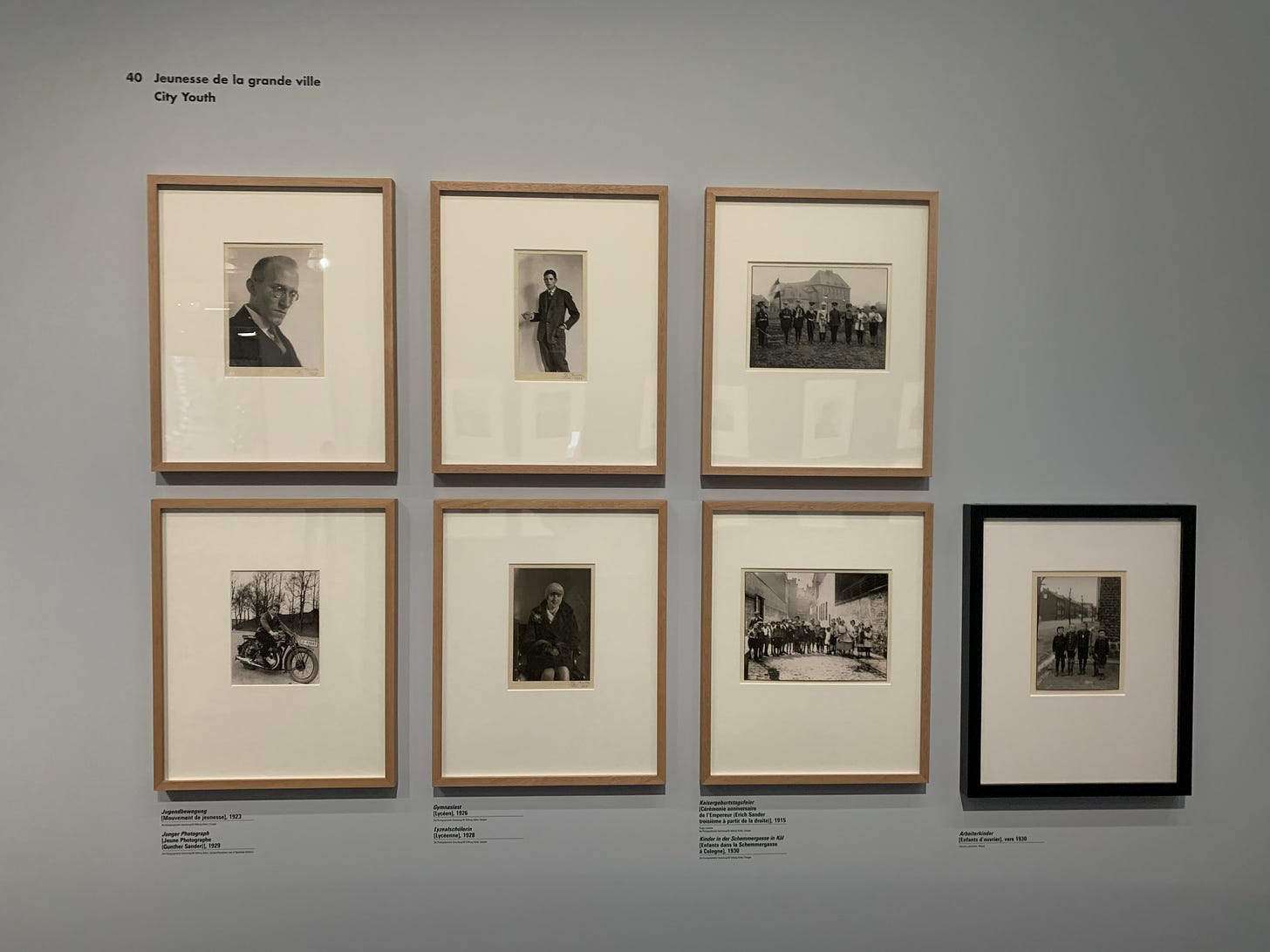

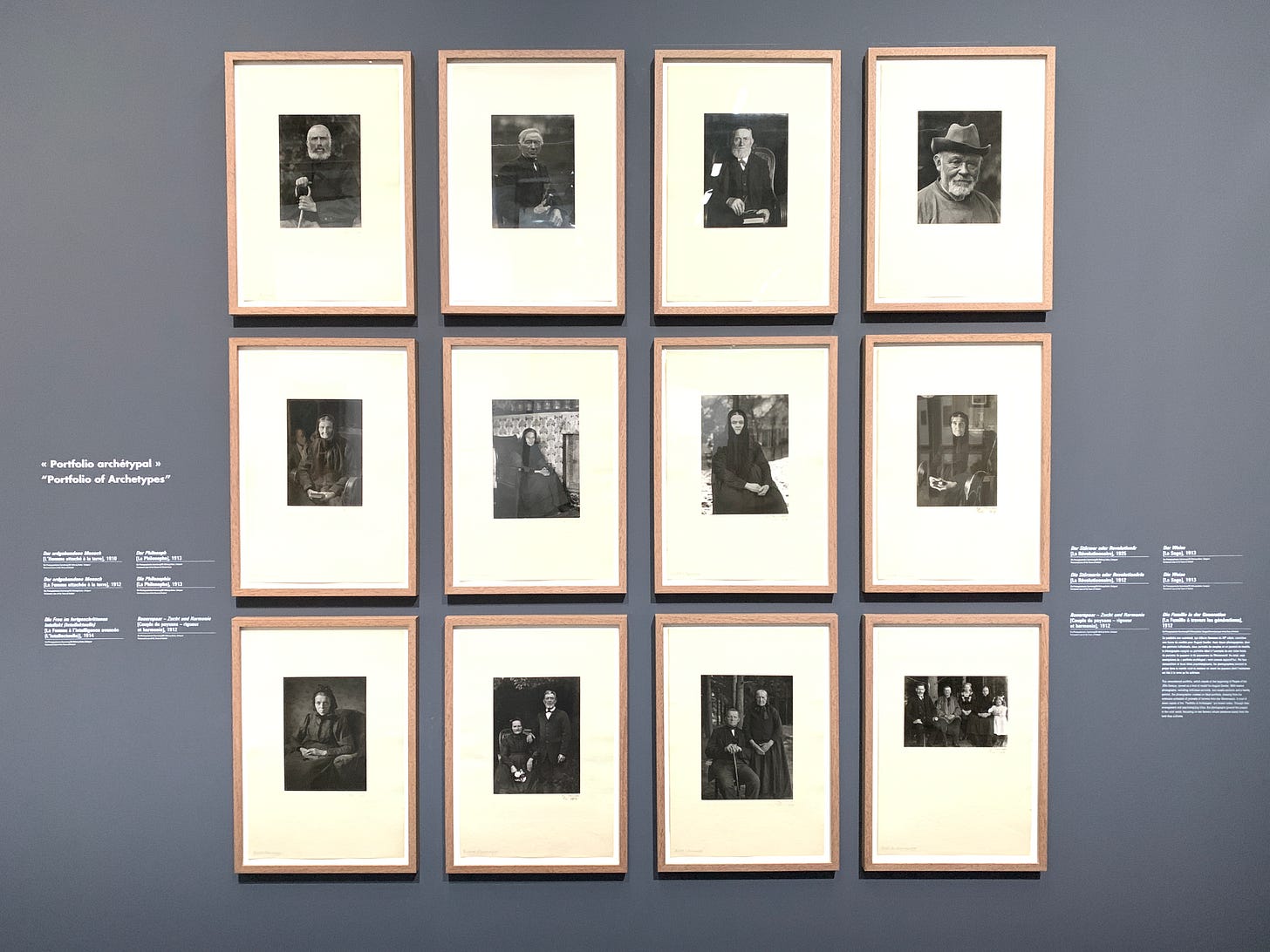

The staged exhibition design is one of such complexity and thoroughness that I confess to having gone twice for a better comprehension of the curatorial purpose. The show consists of a prologue, 12 chapters, and an epilogue: the thematic display goes through the lateral space, and a sort of central gallery with Sander’s photography portfolios complements and intersects the parkour. Though complicated, one may profit from one's desires and expectations: for those who have the time and dedication, getting lost and finding your way through the consecutive chapters is a fulfilling experience that leads to an exhaustive analysis of a society in flux defeated by war.

The antechamber of the exhibition situates us in Germany before the war. Three works embody the time: a famous photo by August Sander in 1914 (a few months before the outbreak of the war) of three nonchalant young farmers, unaware their life was about to change forever; an expressionist self-portrait by Ludwig Meidner, one of the greatest painters of the 1910s in Berlin; and the Dada head of Raoul Hausmann composed of found objects where one finds a total negation of individual expression. These works announce the New Objectivity, the recourse to models, and an abandonment of the individual expression.

Standardization and typology are at the center of the exhibition erasing singularities towards reproducible forms. At the beginning of the show, works such as paintings by George Grosz with faceless schematic human figures in empty urban settings, and Gernd Arntz's development of the Isotype announce the tendency for classification of social classes through standard codes.

This constant social assortment juxtaposes August Sander’s photographic archetype portfolio: farmers, paisans, and artisans. This first encounter with the real confronts us with the actual people who shaped the Weimar Republic, a contrasted representation to paintings and objects.

All through the exhibition, the loss of individuality and the need for typological classification indicate the era to come. From 1918-1930 disciplines like ethnography and anthropology developed, echoed in the encyclopedic photographic project of Sander. People with no name or history are classified according to their status in society and their profession: urban workers, farmers, religious priests, students, politicians, and the elite. Sander's project differs from other similar artistic endeavors, like that of Walker Evans, as it holds a complete annihilation of subjectivity in favor of topologic allocation. This project has a definitive purpose, as well as all the art displayed through the show; utility is a denominator among the disciplines of the time, from art and design to photography, all aspiring for practicality. One may even construe these classifications as immoral, complicit with nazism and antisemitism; although it might come as an overreaching interpretation, one ponders on its lack of innocence all through the show.

Probably the most remarkable section is The Cold Persona: the four deadly years of the war ended in defeat, engendering a general disillusionment. Humiliation breeds a culture of shame. The paintings and photography in this section portray a detached person devoid of all feelings. External representation replaced expression as an almost visual sociological analysis of the subject. Instead of depicting their interiority, they show their position in the social order; the New Objectivity boxes people according to their profession and workplace.

One of the most prominent examples is the famous painting of journalist Sylvia von Harden by Otto Dix. He depicts her without complacency as an emancipated intellectual typical of the Weimar republic: short hair, make-up face, monocle typical of the dandies of the time, and her body hidden under a heavy checkered dress. The artist's gaze focuses on the strange, revealing the mystery of the character. All that was expected of a woman at that time: delicacy, beauty, and charity, is denied in the image of this modern woman smoking alone at a bar table.

The cold person is also revealed in Sanders's photographs comparing the fiction of painting with the document, only to see the same individual; the same woman: masculine, short hair, men's clothing, smoking.

After the war's massacre, women began to take the positions left vacant by men who died in the front. A normative transgression of gender norms and heterosexuality began to take hold in Berlin in the 1920s, with an important homosexual subculture. Seeing women who not only entered the labor market and also won the right to vote in 1918, beginning to dress in pants, shirts, ties, and short hair, developed ideas of revenge by some men.

Otto Dix reveals this discontent in paintings such as that of Dancer Anita Berber, an overtly bisexual star with multiple quirks, caricatured as a personification of sin. All in red, she is presented as a figure out of hell—an incarnation of Babylon, a sinner.

A whole section of the exhibition is dedicated to men's shame and anger for the transgression of normativity through representations of graphic and perturbing violence towards women. A complicit discontent and moral decline towards liberation begin to shape, in disturbingly poignant captures of the time that manifest the cultural malaise of a society.

War, political instability, economic crisis, far-right policies, and social discontent are all evidenced marks of the exhibition, denoting the prognosis of a society that, later on, will go to democratically elect Adolf Hitler. It is almost impossible not to wander through the hundreds of portraits, how many of these individuals will come to be the future nazis.

From a historical perspective, art becomes the symptom of time and provides a better understanding of our existence and how we interpret and interact with reality. Art is such a wonderful token that grants each person what they need. Probably that is the magic of it; but I must believe in its cultural relevance. Not only at its moment of inception but, as we said in our last newsletter, by its plural or disjunctive relationship to temporality. Much of the sentiment expressed by the German society of the 1920s is present in our contemporary world. This show might come as a warning, a diagnosis, or a prediction. An appeal to stop and learn from our past to prevent it from repeating itself.

To see more pictures check my Instagram. 🖖